A daily

Diary

6am Sun

Up. We are vaguely aware that the night

guard is awake and noisily filling the buckets from the standpipe to water the

garden. He leaves as soon as this is

done.

6.30am. Warm shower in our en suite bathroom, where

the plumbing now works (more or less) then Gareth starts on the porridge. This is one of our luxuries. It is sold vacuum packed in tins and costs £2

per lb. So breakfast is porridge with

local Tigray honey and a mug of weak black tea.

7.20am. Gareth goes down the road to catch the

university bus. This can become very

crowded so it’s good to be at the front of the queue and get a good seat.

Viv’s day. Bit of

a housewife type thing going on here. Life

is dominated by the need for clean water, so the kettle is constantly on the

stove (I have a new 2 ring table top model) either boiling, cooling or ready

for the next boiling. This is to kill the giardia

bug that can cause really bad tummy upsets.

Boiled water then gets filtered in a big container. There is usually some sweeping, mopping,

washing, cleaning to do. Dust is blown

in through the constantly open windows and doors and sometimes a jug-full of

earth can get swept up in a day – very satisfying. I like to mop the floors often so that we can

pad around bare-foot on the cool tiles.

It’s nice

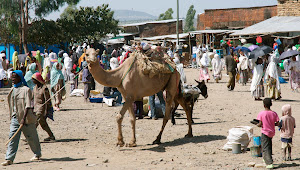

to go out to the shops or the market by 9am before it gets too hot. Whatever is fresh and good quality will

dictate our food for the day. Fresh soft

white bread rolls, or chunky hard rolls, or a big, pizza-size soft bread from

the bakers or ask around to find who is making fresh Injera today. Then to the veg stalls for salad or

greens. A chance for a buna (tiny perfect black coffee with

sugar- a bit like a French express) on the way back home. I have a favourite buna bet (literally a coffee house) where I can sit and waste a

half hour.

Noon. Lunch is ready and waiting for Gareth’s return.

He has to come home at lunch time as there are no toilets at Uni. so it’s a

good excuse to eat together and have a little lunch-time rest. Sometimes we will eat out for a bayonetu (veg

mix on Injera) or ful (spicy bean stew with chillies, rolls and yogurt).

In the

afternoon I may walk the length of Aksum high street to the tourist office to

see friends and talk about our little educational charity, or go to the

Foundation Library where I chat with the staff on an English language

improvement programme. The walk is

lovely, along the tree-lined boulevard (walk in the shade, even if that means

walking in the middle of the road) and there is the choice of about 20 chai/buna/juice/beer

houses, to do a bit of people watching.

It’s not often that you don’t find someone you know for a chat; the

children who know me call out my local name – Viva - It seems to sound good to the Tigrinya accent.

Sometimes, I will chat to the managers of the hotels along the road to

see if there is any work that I can do – proof reading mostly, (some of the

menu descriptions are atrocious – freed fish, chicken sup, brushed beef) but real

work is hard to come by.

Gareth’s day. I get

to the campus at 8am. A week is

dominated by two full days of teaching, which start at 8.30am. These are carried out in the teaching room on

the top floor of the block (windows covered in card and paper to keep out the

sun, one window broken, chairs and tables of poor quality). Most sessions involve lively debates that

offer valuable insight into life as a university instructor. Some candidates have a very high teaching load

and listening to them reminds me so much of colleagues back at UoG. Other days I have a series of tutorials with

candidates who are currently completing action research projects, or lesson

observations to determine the extent to which they have been able to

incorporate active learning methods into their teaching. I’m pleased to say that progress is being

made albeit rather tentatively. In my

office on the first floor, I will meet with candidates and colleagues for writing and planning. I have presented a series of seminars and

written some papers for publication in AKU journals and newsletters. This month

I will run a series of workshops for university staff.

11.30am Time to head back to get a good seat on the noon

bus. Aaaagh, the buses! Large, exhaust-belching monsters. Built to

seat 50, regularly takes 75! If I’m lucky, I’ll catch the ‘executive’ bus which

is smaller, cleaner and an altogether more pleasant ride. Conversation is lively

and often has to compete against loud music from the radio but even with all

this going on the fortunes of Arsenal, Manchester Utd, Manchester City and

Chelsea are obviously being discussed. Shame I can’t join in. Lunch and a rest, usually at home, and catch

the 1.30pm bus back to uni. for afternoon teaching or planning.

5pm and it’s back home for supper and a film on the

computer or an evening of peaceful reading or scrabble, or pop down to the

draught house for a beer or to the local hotel for a football match. There you go – nothing too taxing or

exciting!!

7.30pm Sun

down. Our night guard arrives to patrol the

compound. He stays awake until we are

both in bed and copes with anyone knocking on the compound gate, and then he

unrolls his mattress on the floor and sleeps under the outside stairs. He is also a priest at the cathedral, so on

occasions he has a sing song (not terribly melodic) to accompany the local

wailing priest from Santa Micael on his loud-hailer, or he reads his bible out

loud in Ge’ez. All quite gentle and

calming.